PART ONE:

I’ve never met secondary English teacher Jacqui Moller-Butcher but I’ve known of her since she first raised worries about her observations of ‘look-alike reading’ in an online discussion via the blog of popular KS 3 blogger, David Didau. At that time she was addressing some of author Michael Rosen’s posts as he is someone who has gone to great lengths in England’s context to challenge the official guidance of ‘systematic synthetic phonics’ provision and the introduction of the statutory Year One phonics screening check. From Jacqui’s personal experience, she understands the promotion and importance of quality phonics provision and was clearly worried that a popular children’s author with great ‘reach’ to teachers, and others, would actively undermine the need for systematic phonics provision in our schools.

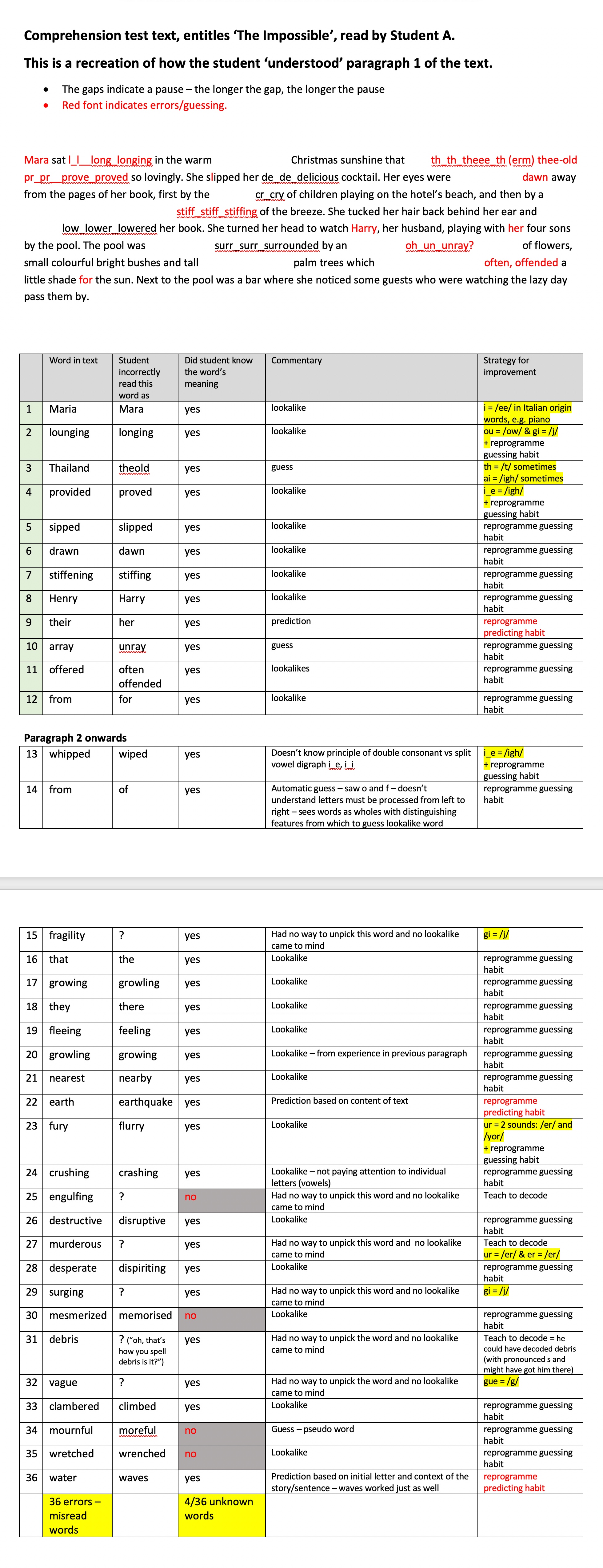

Some time later, Jacqui got in touch with me to let me know that she was actively promoting my self-study Phonics Training Online course to her secondary colleagues and to local secondary headteachers. Apparently, some Learning Support Assistants in her school had already taken the initiative to sign up as individuals. Jacqui described the school’s findings of some Year 7 students when they read aloud. The intent was to discover what kind of word-errors they made in reading and why, and how, they might be making these errors. In response, I asked if Jacqui would provide a guest-post and share these findings which are very important indeed. They certainly support my suggestion that ALL teachers should be trained so that they are knowledgeable about the English alphabetic code and how to teach, support, and/or remediate reading and spelling. Surely all teachers need the level of knowledge and understanding in the field of foundational literacy to meet the needs of all children and young people as required.

In the subsequent exchanges with Jacqui where she kindly provided me with a guest-post, I said her work and findings are so important that a ‘post’ alone would not be sufficient, and that her findings need to be printable as a ‘paper’ and so Jacqui has kindly provided her work for both guest-post/s and as papers. I do hope that anyone reading these will be prepared to share them widely as there are great implications here about the need to expand teacher-training in this field for all sectors and not just early years and infant staff. We need to build on what we know to date – and appreciate that we still have some way to go before we reach optimum teacher-training and teaching/supporting our children appropriately, as required.

About Jacqui:

I first noticed look-alike reading when I was out of the classroom, at home with my four children under five years of age! I was working voluntarily as a tutor with friends’ children of all ages. Because of my phonics training for KS3 at Phoenix High School in White City where I was an assistant head (I received my training from Ruth Miskin herself in 2002), many friends asked me to help with early years reading issues. With four children, you find that the number of fellow parent friends rapidly increases, and so I was asked frequently. I had never taught 1:1 before and this gave me the space to notice all manner of interesting things which I started to record. I could compare this directly with my own four children who all learnt phonics from me from age 3, and so an accidental, unofficial research project began.

As a secondary teacher, I was asked to work with older children at the same time, of course, for KS3 issues and for GCSE preparation. That’s when I realised that children of all ages were doing exactly the same thing – guessing words as look-alikes. This was something I had not noticed in all my years of teaching as an English teacher. My friends’ six year olds were trying to read words in the way that fifteen year olds were. I started to listen to all of my 1:1 students read aloud to spot how they read and identify what errors they made and why; then I was able to help them unlearn their guessing habits and relearn forgotten or learn new code to fill gaps. At the same time, I realised that my own children were being taught multi-cueing strategies at primary school and the whole picture crystallised. All of these accidental life events and professional strands came together at once and gave me a clear understanding of issues I had never understood before.

Further, Jacqui has concerns about the guidance provided to improve reading standards by another popular KS 3 blogger, Alex Quigley, and she describes these concerns based on observations and detailed assessments:

I attended Alex Quigley’s Closing the Literacy Gap webinar recently. He outlined 12 important reading strategies that weak readers don’t use: skimming and scanning, questioning texts, evaluating texts, possession of tier 2 and 3 vocabulary, etc. He said we need to model and teach these strategies explicitly. The breakdown of the twelve strategies, along with some practical tips, was the main thrust of the seminar.

Teaching the suite of advanced reading strategies through modelling and explicit teaching made up a good proportion of the modules in the KS3 Literacy Strategy many years ago, and, as a literacy consultant of old, I’m still very enthusiastic about the ideas and modelling approach. The new thread of focusing on tier 2 and 3 vocabulary is an important addition. I know that closing the vocabulary gap has been a major thrust in many schools in recent years.

However, despite presenting the statistic that 25% of 15 year olds have a reading age of 12 and under (I’m sure that’s right, a conservative percentage for many schools like mine, in fact), Quigley didn’t emphasise the crucial role that partial alphabetic code knowledge, guessing habits or slow reading speed play in deficit reading ages, nor what secondary teachers need to do to address these issues.

This doesn’t surprise me in secondary training because an emphasis on the alphabetic code and long-overdue recognition of the scale of the guess-reading problem is still only just emerging for the secondary sector. Quigley may have decided that, for a mixed subject audience, it might prove counter-productive to delve into the mechanics of reading. But I was left feeling frustrated because encouraging children who don’t read accurately or quickly to skim or scan or summarise is, perhaps, putting the cart before the horse, and may actually compound frustrations and self-esteem issues.

One of the last boys I worked with 1:1 before lockdown read aloud to me a Y9 comprehension test paper which had been set for the class. He guess-read incorrectly 36 words out of approximately 400 so just under 10%. He read most of the words as look-alikes – or couldn’t attempt to pronounce them at all – and often didn’t stop to think when they didn’t make sense. At other times he paused for lengthy periods while he tried to think of a lookalike word that would fit the pattern of the word he was looking at. It was a slow and painful process. An analysis of his reading is HERE.

I was amazed to find out that, when I read the words back to him correctly, he was able to explain the meaning of all but four. That’s 32 words he didn’t comprehend because of deciphering issues when he absolutely did understand them, based on his existing vocabulary knowledge.

Teaching this student the meaning of more, richer, higher tier vocabulary is no bad thing, but it won’t help him to decipher the new vocabulary in print or to encode it in his writing. There’s much he understands in his head already that he can’t access in print on the page.

However, more worryingly, this student is not ready to be taught to skim or scan, no matter how well I model the processes, because he has underlying, more fundamental issues: a guessing habit, gaps in his knowledge of the alphabetic code and slow reading speed, and all these need fixing first. Trying to teach him strategies that he’s not equipped to manage will result in yet more reading failure.

Teaching weaker readers the strategies that stronger readers use might be an upside down – or back to front – approach, I’m not sure which it is! Is it the case that weak readers can’t skim and scan because they haven’t been shown how to, or is it because they aren’t strong, efficient readers? Isn’t being able to skim and scan and ask questions and evaluate texts the product of being an accurate, automatic, fast reader – it’s possible to do these things when reading the print is effortless, and it’s not possible when it isn’t.

There seems to be a priority sequence for interventions; teaching some of the higher order strategies depends on fundamentals being already in place. The problem is that, typically, we aren’t trained to tackle decoding issues in secondary schools and we’re identifying the full extent of the problem either. We have to find ways to overcome that.

Right at the top we have to:

1. Make sure all students can decode spellings well. Plug alphabetic code and morphemic knowledge gaps as required.

2. Make sure all students do decode. Stop the guessing and predicting habit. This is widespread and absolutely not just a special needs issue.

3. Find ways to get students to read more often to practise reading print in order to increase speed to at least speaking speed: reading aloud @ 180wpm or faster.

4. Teach and promote vocabulary extension in lessons across the curriculum.

5. Once students can read accurately, without guessing and aloud at 180wpm+, teach the more advanced reading strategies.The sheer extent of guess-reading and the number of students reading aloud @ sub 150 wpm was a shock to us when we introduced 1:1 testing in September – for us it’s nearly 30% of our KS3 students. The issue of accuracy and speed isn’t one for SEND; it affects the very 25%+ who Alex Quigley refers to. We need to make most progress and effect change in guaranteeing the 3 fundamentals of good reading before teaching the 12 advanced strategies to the target 25%.

And, if we do, we might find that some of the higher level reading strategies take care of themselves…

PART TWO: The harmful legacy of multi-cueing and its evolution into look-alike reading – a secondary school perspective

by Jacqui Moller-Butcher, secondary English teacher 18.6.2020

Pingback:PART TWO: 'The harmful legacy of multi-cueing and its evolution into look-alike reading – a secondary school perspective' by Jacqui Moller-Butcher - The Naked Emperor

It’s very sad that after all these years we’re still confronted with the same problem, which is why Debbie, Maggie, Fiona Nevola, me, Ruth, Marlynne Grant and so many others have worked so hard to try and turn this thing around.

All of the errors Jacqui highlights above are described in Diane McGuinness’s Chapter (2) ‘How do readers read’ in Why Children Can’t Read. I’m always urging people who don’t know and want to know why we have so many problems with teaching children to read to pick up a copy of McGuiness’s book and find out what it’s all about.

Of course, if those people read what Debbie has to say, they’d have an even better understanding.

Thank you, Jacqui, for the post and thanks, too, to Debbie for giving it space.

We fight on!

Best regards,

John

You’re right, John, and thank you for leaving a comment. Maggie (Downie) has just commented via Twitter after reading Jacqui’s post that she was saying the same thing 10 to 15 years ago. It was longer than 15 years ago.

One would have thought that now 14 years after the Rose Report, we would have phonics provision well-addressed in England. Clearly not so…

What Jacqui documents is sadly very familiar. As an FE tutor in the 90s, I was tasked with finding increasingly creative ways to get GCSE English resit students’ grades to a C. This ignored monumental gaps in what I would have called ‘basic skills’ back then, but what I now know to be gaps in alphabetic code knowledge (thanks to Debbie for that). This led to a journey which included training funded by the taxpayer following the Rose review. The aim of this training, a post as a Literacy and Dyslexia Specialist in a school, never came to fruition despite Rose’s recommendation that this was needed. 14 years on, I am still working to reach those for whom literacy struggles limit their life chances. Thanks Debbie, Jacqui and others for keeping the dream alive! We WILL get there!