For PART ONE of this topic, introducing Jacqui Moller-Butcher and her work and worries about ‘look-alike reading’, click HERE.

by Jacqui Moller-Butcher, June 2020

Please click on the link above for Jacqui’s full paper in printable format as it includes a chart of the detailed findings of the word-assessments of Year 7 students. For anyone with an interest in these findings, please circulate the paper and links to Jacqui’s guest-posts widely.

Here is Jacqui’s paper as a post:

The harmful legacy of multi-cueing and its evolution into look-alike reading – a secondary school perspective

by Jacqui Moller-Butcher, secondary English teacher 18.6.2020

Twenty-two colleagues at the secondary school where I teach English started a 20+ hours online phonics training course in the second week of lockdown, and the effects are beginning to show. Many of us have children, and so the training is interesting as parents too. One of the team emailed today to say that while reading with his primary-aged daughter, it became clear that she has been taught to multi-cue and was using images on the page to guess words, rather than using phonics to read them. He said he simply wouldn’t have noticed that before.

Multi-cueing. What’s wrong with it?

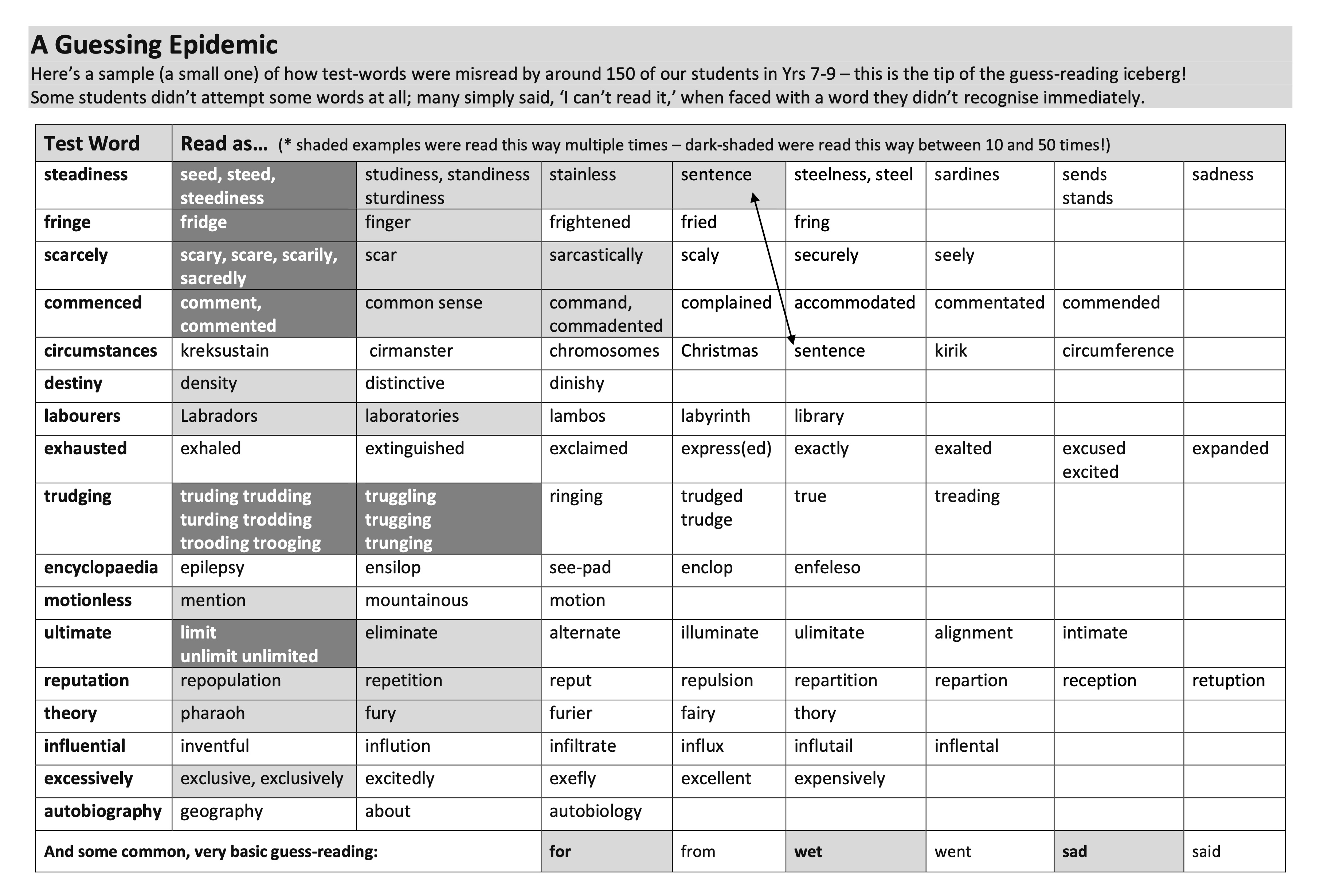

We tested our Year 7 cohort on arrival this year for gaps in their knowledge of phonics and to assess reading age. For the first time, tests were taken 1:1 with trained LSAs (Learning Support Assistants) who listened to every word and sound uttered, all of which were transcribed – rather unusual as a testing process in a secondary school, where tests usually assess comprehension, and are often done all at once and in silence. We introduced this system to see and hear how our students think when they read, and to learn what ‘wrong’ actually means for every one of them: why are they wrong and how wrong? From this approach, we have harvested useful and fascinating information at an individual and cohort level.

It became immediately clear, for example, that for around 30% of our students, guessing was the principal strategy for ‘reading’ unfamiliar words. Of course, there were no pictures on which they could base their guesses, true of many secondary school texts, especially in English, and so students guessed words by their most prominent, recognisable features, as if identifying a face by hair, eyes and nose.

The hair, eyes and noses of words seem to be the first, a middle and the final consonant, or at least one near the end. Consistently, vowel spellings are ignored in this ‘facial recognition’ process; it seems our students see many vowel spellings as foreign, indecipherable code, or they barely notice them at all. From these findings, we think 30% of our students see many words like this:

exostиd

moйшanlэss

repюtэйшan

If you can read English and Russian, you’ll be able to pronounce these words accurately (as the real English words they are), because I’ve used the closest possible corresponding Russian symbols to represent some of the English sounds. The English spellings I’ve replaced are those our students commonly struggle to recognise – in these words, the spellings: au, e, o_i, ti, u_a, a_i.

We’ve deduced that in order to read the all-too-many words that look like this, students do what you have probably just done – they make a ‘look-alike’ guess based on 3-4 recognised consonants.

Worse, it seems that many of our students think it’s normal for words to look like this. They aren’t puzzled when they meet them, and they rarely hesitate to say what they see; they think they are supposed to guess. They seem to believe, we’ve found, that this is what reading is.

I gave the three words above to our secondary teaching staff in INSET recently, and asked them to do the best job they could of reading them aloud. The full extent of ‘readings’ offered were as follows, and many were repeated around the room:

• exostиd: existed, excited, excused, exhausted, exostand (and other pseudo words)

• moйшanlэss: mountainous, monotonous, Mona Lisa, money-less,

• repюtэйшan: reptilian, reproduction, repetition, reputation, reprowan (+ more pseudo words)

I knew there was one Russian reader in the room and he was able to pronounce all three perfectly, recognising the English words that the mixed spellings represented, because he knows English and Russian code. Quite simply, he possessed knowledge of the necessary code to unlock the print. Everyone in the room was a degree graduate of one subject or another, all very well educated, but few could pronounce the words correctly, so they could not access the meaning, try as they might.

Our Russian reader, when prompted, revealed the words to be: exhausted, motionless and reputation. Was he cleverer than everyone else in the room?

The words were all easy, known words – words in every teacher’s vocabulary, and yet with possession of partial code, some very clever teachers couldn’t recognise the words they knew. This is the predicament, we’ve found, for around a third of our KS3 students. Their vocabulary and knowledge has continued to grow, albeit slowly in some cases, since early years in primary, but, in many cases, their understanding of the written code has not, and they have continued to practise their guessing habit. They are able to read less than they know. The huge problem for us is that practice has made permanent.

If there had been a picture for each word (though a picture to convey reputation is not easy to come by), our teachers might have been able to guess each word, but that strategy wouldn’t have enabled them to decode the Russian symbols, much less learn them.

It also wouldn’t have helped the teachers to decode the Russian symbols if the words had been written into full sentences, but would they have been able to guess the words? Let’s try that…

Here’s a sentence from the GCSE text ‘Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’. In our school, all students in Y11 will study this book:

“Men have before hired bravos to transact their crimes, while their own person and repюtэйшan sat under shelter.”

And the GCSE text ‘A Christmas Carol’:

“But scorning rest, upon his reappearance, he instantly began again, though there were no dancers yet, as if the other fiddler had been carried home, exostиd, on a shutter, and he were a bran-new man resolved to beat him out of sight, or perish.”

Does it help a lot if the unfamiliar-looking words (remember, although unfamiliar-looking, all three are known vocabulary) are presented in sentences, in context? Well, clearly, it depends on the sentence. In a simple sentence, in a simple text, perhaps. But it requires more than a bit of thought to work out the mystery words in the contexts above, and it’s probably fair to say that it certainly doesn’t help ‘a lot’. Add to that the fact that, for many students, Dickens and Stevenson’s sentences above would contain other ‘Russian-looking’ words, it becomes clear that recognising known words from context is an unhelpful and inefficient strategy when rapid code recognition would unlock words so much more quickly.

In short, it’s a whole lot easier just to recognise words from their letters, in an instant, and it’s a crying shame if you can’t when mystery words are words you already know and understand.

The texts children face in secondary school are sophisticated and complex. Therefore, it’s crucial that they are able to decipher and recognise words they do know instantly, without effort, so that they can focus their brain power on deducing the meaning of the vocabulary they don’t.

The idea of our INSET activity was to show secondary teachers how around a third of our students actually see many words on a page, and to allow teachers to experience the difficulty of ‘reading’ with only partial knowledge of the alphabetic code. Put in this position, our teachers automatically used the common student strategy of visual guesswork.

Interestingly, the guesses of our well-educated teachers were very similar to – or exactly the same as – those of our struggling readers who, in assessment, misread exhausted as: exhaled, extinguished, excited, exclaimed, expressed, exactly, exalted, excused and expanded. (There’s no lack of good vocabulary there – just a lack of decoding.) Our students in assessment misread motionless for mention, mountainous and motion. And they misread reputation for repopulation, repetition, reput, repulsion, repartition, repartion, reception and retuption. In fact, arguably, our struggling readers performed at a similar level to our teachers; they came up with mostly real words (but some pseudo ones too, as did the teachers) that look a lot or a little like the target word, but aren’t close in meaning at all.

Any reader, well-educated or not, with good general knowledge or not, when guessing words from prominent features, will draw on what is often an extensive bank of look-alikes. Because there are so many possible words, it was just pot luck, rather than a matter of IQ, whether our teachers hit on the right word with their first look-alike or not.

So far I’ve emphasised the similarities, but the key difference between our students and our skilled-reader teachers was one of attitude, not strategy; teachers instinctively knew it wasn’t right to read in this way and didn’t like the experience, but they didn’t have any choice when faced with substituted spelling symbols. They said it felt unnatural. They groaned and grumbled. This is probably because skilled-readers aren’t hard-wired to guess. They know that guessing isn’t reading. Skilled readers instinctively know the job is to decode when a word is unfamiliar. A third of our students don’t.

Next I gave the same teachers these real English words:

archimage

coggly

mammothrept

sesquiplicate

Now they were much happier. They pronounced all words easily and fluently, after just a moment’s analysis, with only minimal variations in pronunciation and emphasis around the room. All pronunciations were plausible, and yet nobody had any idea what the words meant, despite being real English words. Our skilled-reader teachers knew in an instant that they didn’t know the meaning of these words. They didn’t feel confused or reading-disabled, as they had with the words they couldn’t decipher, and they didn’t express frustration at all; in fact, many were very intrigued.

This is perhaps the most destructive consequence of the guessing legacy: a skilled reader knows when they don’t know a word. Our struggling readers, through guessing, can’t decipher words that they know well and words they don’t know at all – they aren’t aware of the difference. If students misread an unknown word as a known word, they won’t (and don’t) stop to deduce meaning from context, even when it might possible. Meaning becomes mangled, confused, and they won’t (and don’t) know why. Reading like this is a horrible experience. Trying to make sense of increasingly complex and sophisticated texts in subjects across the secondary curriculum in this way is tortuous.

If a student arrives in Year 7 guess-reading, their reading age will plateau without extensive exposure to text (and if they haven’t done enough reading to deduce the code through osmosis so far, evidence suggests that they’re unlikely to develop the reading habit post Y6), while their knowledge and understanding will continue to grow, and so the divide between what they know and what they can read and write grows ever greater – as does their frustration, their diminishing self-esteem and, most obviously, their disruptive behaviour and a dislike of school.

In secondary schools, students who haven’t yet learnt to read fluently, who achieve low marks on a comprehension test or in a reading age test where no one listens to the child attempt to read, so cannot diagnose why an answer is wrong or how wrong, are often perceived as learning or reading-disabled. The problem is seen to be in-child. Secondary teachers rarely listen to students reading aloud in an extended way, especially struggling readers who avoid reading in class, and little time, therefore, is given to analysing how students read. This means that secondary teachers, untrained in this field, may not understand that many students are reading the wrong way, applying a flawed multi-cueing approach, guessing words as look-alikes, rather than deciphering the letters in words, and that the problem is one students cannot fix for themselves, not without direct and explicit intervention.

More library time, buddy readers, author visits, reading logs, World Book Day and ERIC won’t correct flawed reading habits. Accurate diagnosis, replacing guessing habits with decoding habits through regular practice with a trained professional and reinforcement in all classrooms, and filling gaps in students’ understanding of the alphabetic and morphemic code will.

If students are equipped to decode accurately and effortlessly, and they know that guessing words like recognising whole faces is not a part of skilled reading, they are able to identify an unknown word straight away, and so they are empowered to pause and deduce meaning from context if they can – or look the word up, just as skilled-reader teachers do, if they can’t.

The multi-cueing strategy which may seem to work very nicely, quickly building self-esteem in Year 1 or 2 or even 3, where comparatively little vocabulary is needed to read age-appropriate books, where sentences are largely simple and short, and where pictures abound, creates a harmful legacy for over a third of students in our school, and has a devastating impact on their secondary school experience, an experience that is extremely difficult to navigate as a struggling reader.

Children are prone to guessing because it’s quicker and easier than the hard work of decoding.

Multi-cueing instead of decoding is like taking a short cut across the garden, because taking the path around the edge is too long; it’s immediately gratifying, and it feels like it gets you where you want to go, but soon enough the grass will stop growing and ever-increasing bare patches are left behind. There are long term consequences that aren’t foreseen when taking those first steps.

Children need no encouragement to guess. If they are encouraged, they absolutely will, but they will do so at the expense of fostering the reading habits of genuinely skilled readers, and they may never fully master or apply the alphabetic code. For a fast track to what seems like success, for the glow of ‘feeling and sounding like’ a real reader quickly, for the pleasure that pretending to be a fluent reader brings at the outset, children are at risk of paying the heavy price of low self-esteem, disaffection and reading failure later as a teenage student in secondary school and, worse still, as an adult in real life.

For those intrigued:

archimage a powerful magician or wizard

coggly unsteady, wobbly or shaky – ‘She sat cocked to one side in a coggly canoe’

mammothrept a spoilt child

sesquiplicate relating to or involving the ratio between the square roots of the cubes of given terms; i.e. the sesquiplicate ratio of given terms is the ratio between the square roots of the cubes of those terms

Note from Debbie after Jacqui’s guest-posts were shared via Twitter:

There has been considerable interest in Jacqui’s findings notably from teachers and senior managers in the secondary sector.

But most significantly, an amazing stalwart campaigner for research-informed reading instruction and phonics from the USA, Don Potter, immediately contacted me with this personal message:

Name:

Donald PotterEmail:

don@donpotter.netSubject:

Look-AlikeMessage:

Debbie,The article on look-alikes is fabulous. Helen Lowe wrote about this way back in 1958. I have similar lists of common errors: I call it Squirrelitus because my students almost always read “squeal” as “squirrel.”

Please do take an interest in who Don Potter is and his extraordinary contribution to the reading debate over many, many years. How can it be we are still having these word-reading problems for so many of our learners – which so many in the teaching profession simply don’t know how to recognise and/or how to address?

Pingback:PART ONE - Guest post: Introducing Jacqui Moller-Butcher and her extraordinarily important findings (and suggestions) regarding 'look-alike reading' in KS 3 - The Naked Emperor